Differing perceptions on conserving nature

A Tharu village in the buffer zone of Chitwan National Park, Nepal. (photo: Ben Robson)

The natural world has constantly changed and developed as a result of both natural and anthropogenic influences over geological time [1], the notion of conserving and preserving landscapes for future generations is however relatively recent. In particular, a distinction exists between perceptions of how “pristine” landscapes should be conserved between the more developed “Northern” countries and the less developed nations in the “South.”

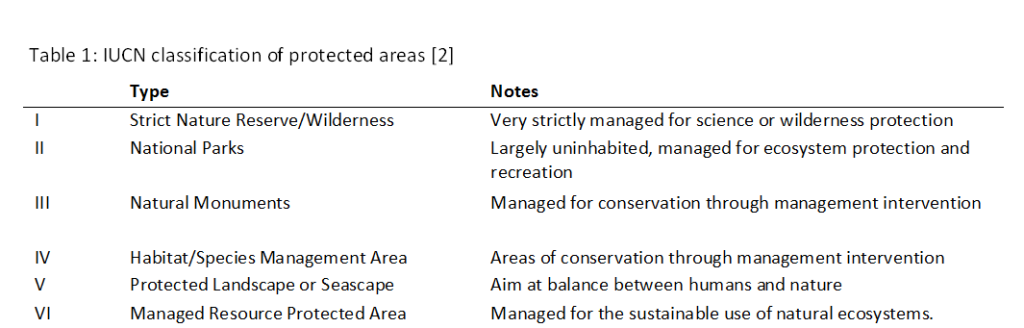

Countries in the North generally moved from a predominantly rural population to a more urbanised population during the industrial revolution, as such when national parks and conservations were established in the mid-20th century, significant populations were already settled within the new national park boundaries, thereby limiting the amount of conservation that could be carried out. National parks in Western Europe generally conform to a grade V classification according to the IUCN classification scheme (table 1), aiming to find a compromise between the needs of both mankind and nature.

75% of land within English and Welsh national parks is privately owned meaning it is seldom that pure «wilderness» is found. Activities such as farming, mineral extraction or power generation are in some cases permitted within the park, but economic activity that that could aesthetically impact the landscapes that we associate with our cultural or national identity are limited [2]. and steps are taken to preserve the building style, land-use and character of the area. For example, many would associate the Lake District National Park with William Wordsworth, traditional rustic farming, the rolling hills of England and relaxing around the lakes than they would with untouched nature. It could be argued that most British, and to an extent European national parks are therefore preserving a human-influenced landscape that we feel is in danger rather than a wilderness. Economics can be one of the biggest driving factors in establishing new parks, revenue from tourism has helped create parks in Australia, the UK and Canada during the last 20 years[2].

The Lake District, UK, has been a popular destination long before it was designated a national park in 1951. William Wordsworth famously wrote «I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud» about the area in 1802 (photo: wikipedia)

Our Tharu guide, Raju, had his father killed by a wild elephant. (Photo: Pål Ringkjøb Nielsen)

National parks in developing countries on the other hand were often established after those in industrialised nations and while a higher proportion of the population lived rurally. Some communities therefore underwent challenges to their livelihoods, or in some cases were forcibly evicted in favour of conservation [3]. Following the establishment of the Chitwan National Park in Nepal, the Tharu people faced restrictions on the amount of biomass and fruit that could be harvested, while fishing, hunting, and the amount of grazing land were also restricted [4]. Since 1964 over 22,000 Tharu have been removed from the park. Despite initial high expectations, many Tharu found the compensatory land was inadequate in terms of soil quality, resources, location and cultural value. Additionally, the re-location has affected the community social structure by mixing indigenous and hill castes [4]. The fate of the Tharu people is just one of many examples of local people being marginalised in favour of conservation, where following resettlement the population are forced to become less self-sufficient without the natural resources they previously relied upon.

It’s not just the understanding of national parks that differ between the “North” and “South” when it comes to how conservation is perceived. There is also a large distinction on how the conservation of large mammals. Despite a population of just 35 to 52 wolves, Norway kills over 25% of the population each year, and also permits the cull of bears, wolverines and even Golden eagles that have killed reindeer [5]. The wolves are exterminated based on the risk posed to farmers and their livestock. In reality however no one has been killed by a wolf in Norway since 1800 and of the 26,512 cases where farmers were richly compensated for livestock killed by wolves in 2012, only 1809 (7%) cases presented carcasses. A further 20,000 cases were rejected by the authorities [6].

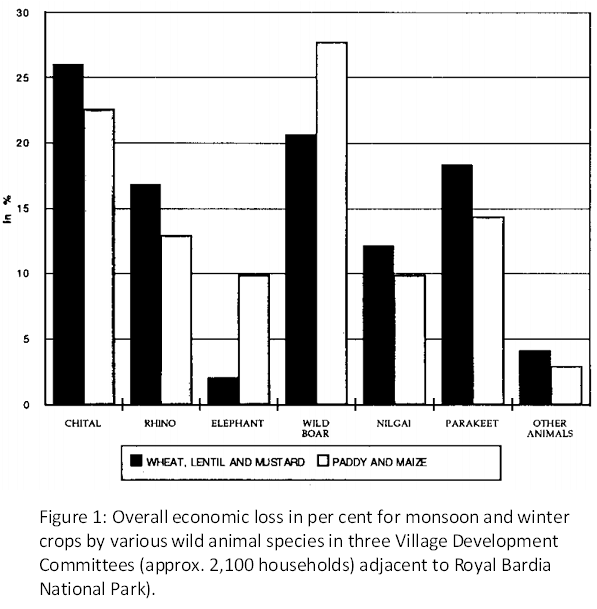

That one of the world’s richest countries can kill a “critically endangered” species seems contradictory when you consider how Norway is an avid supporter of conservation in the developing world. Human-wildlife interactions are a serious problem in Nepal where 21 people were killed by wild elephants between 2008 and 2012 [7] while crops such as rice, lentils and wheat are frequently damaged by wild animals [8]. Some have argued that if less developed countries were to use similar tactics for protecting their agricultural livelihoods there would be widespread commendation [6].

Of course, the Scandinavian countries do many great things for conservation both at home and abroad, but I think that if conservation of nature is to be addressed on a global scale then we need a global consensus of how to construe conservation. We need to decide what landscapes we are conserving and whether they should be conserved due to their importance for wildlife and nature or due to their cultural value to us and whether there should be a distinction in conservation techniques between landscapes. Similarly we cannot expect poorer nations to act on our public perception and advice concerning conserving of large mammals when we take such drastic action on curtailing animals perceived to be a threat within our own territory.

- Hannah, L., et al., Conservation of biodiversity in a changing climate. Conservation Biology, 2002. 16(1): p. 264-268.

- Woods, M., Rural geography: Processes, responses and experiences in rural restructuring. 2004: Sage.

- Brockington, D. and J. Igoe, Eviction for conservation: A global overview. Conservation and society, 2006. 4(3): p. 424.

- McLean, J. and S. Straede, Conservation, relocation, and the paradigms of park and people management – A case study of Padampur Villages and the Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Society & Natural Resources, 2003. 16(6): p. 509-526.

- Monibot, G., Norway’s plan to kill wolves explodes myth of environmental virtue, in The Guardian. 2012: London.

- McPherson, B., Den norske ulveløgnen, in Aftenposten. 2013: Oslo.

- Pant, G. and M. Hockings, Understanding the Nature and Extent of Human-Elephant Conflict in Central Nepal. 2013.

- Studsrød, J.E. and P. Wegge, Park-people relationships: the case of damage caused by park animals around the Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. Environmental conservation, 1995. 22(02): p. 133-142.

Nice piece of information!

Issue of severe human-wildlife conflicts in Nepal is highlighted here as a case of unsustainable biodiversity preservation in DEVELOPING nations, which followed the conservation models of the DEVELOPED nations without recognizing the local/regional contexts. For me, conservation challenges in there regions are rooted in the weak implementation of the sectoral as well as cross-sectoral regional policies rather than the conservation modality itself.

For instance, not only the small patches of the habitats/forests so called Protected Areas (PAs) but the whole low land region in Nepal has long been the dwelling place of the wild species even long before human settlement in the region. Rapid human encroachment in the luxurious forests over past 4-5 decades to convert it into the farmlands severely damaged the wild habitat. Vast tract of the forest in the low land region of Nepal was rapidly fragmented by the farmlands within only 20-30 years. A few PAS in those regions are now acting only as small islands in the ocean of human settlement, which too small to keep the wildlife, especially the larger mammals like elephants. This results into severe human-wildlife conflicts.

So, rather than trying to follow the conservation modalities depicted in the ‘BOOKS’, the stakeholders from the ‘DEVELOPING REGIONS’ need to change their perceptions, by thinking a step forward toward sustainability. Some of the such initiatives can be: effective implementation of the biodiversity related sectoral-cross sectoral policies; participatory management of the whole landscape that can address the need of both human as well as the wildlife; regional collaboration for the conservation and development of the region through trans-boundary conservation and development networks.

Great addition there Kuber, I think you know a lot more about this than me! But I think it is especially interesting that the protected areas aren’t large enough to contain a natural habitat for lots of the animals. I thought it was intriguing that a lot of «eco-tourism» promoted in the area actually leads to much more rapid encroachment on wildlife, by each lodge trying to find a remote area within the park close to the wildlife. I heard from a family I regularly stay with in Kathmandu that sometimes hotels would make feeding or drinking areas within view of the hotel to attract wildlife. Also isn’t it the case that all tourist infrastructure from within Chitwan was removed a few years ago? So that now many of the luxury lodges have been forced to re-locate to the edge of the park. I wonder whether this will have a substantial benefit on the park or not.

This topic is very interesting and is a cause for discussions. You said that: <>. You mentions «we» as the people have to decide, and I agree in that. But all of these problems are caused by us, the people. Because we as people have the right to live here on the planet as well, but we are becoming so many, over 7 billions. And where should we go and more importantly, where are we supposed to get our food from? This balance is difficult, and we cannot please everyone. But you are right! We need to decide what to do and what we should conserve. But I think the balance there is going to be a challenge.

Very interesting article Ben! I would easily mistake you as a human geographer now 😉 I guess there was predators in England also at some point in the past, could you imagine them reintroducing them again?

Thank you for this well written blog! To be honest, befor the lecture I have never really thought about how paradox our pursuit of conservation in the „southern countries“ is, if you compare it with our often missing willingness to accept any disadvantages or changes, that would come along with stricter conservational efforts here in the „northern countries“. The wolf example shows impressively how we are treating „here“ and „there“ differently. For me this is one of the interesting points, I am sure, I will remember from the global change ecology course!

Very interesting discussion and examples on North South perception on nature conservation. Yes, Chitwan National park, the first national park of Nepal established in early seventies, was much influenced by ‘Yellowstone’ model and mainly aimed at conserving tiger and rhino. As pointed by author, people were evicted, rights of local resource users were curtailed and cultural practices were hampered. Now, Chitwan national park has widely been applauded for its performance in conserving tiger, rhino, crocodiles, birds etc. Tourism has helped in local economy, and buffer-zone program has given almost 50% of revenue of national parks to local communities. However, people-wildlife conflict still is a serious issue and authorities need to do much to secure local people’s right to survive while conserving large mammals.

There has been a significant shift in Nepali conservation policies since establishment of its first national park. These shifts have somehow ‘blurred’ the distinction of North South perception pertaining to conservation. Concerns over human rights and use right of local people, civil society organization, and democratic institutions are always growing in Nepal. Growth of such institutions has contributed in considering local peoples’ right as a key issue in conservation planning. Currently conservation models based on ‘Integrated Conservation and Development’ is also in practice and people live in conservation areas, practice traditional uses of resources, play role in conservation and get benefit of conservation.

As pointed by Author, currently there are different conservation models that range from ‘Yellowstone’ model to ‘Integrated Conservation and Development’. Idea of fenced and fortressed conservation is weakening and people have been integrated in recent conservation instruments.

I somehow cannot understand how could be even possible that Norway or any other European country is planning to kill even one wolf if population is around 20-30 wolves… It is impossible that 20 or 30 wolves can make some damage to economy, and if farmer get compensation for killed livestock which is anyway more probably killed by trafic accident,train etc. then i think that hunting for wolves (legally) is nonsence. But the same problem is also in another countries like in slovakia, where is the same problem also with bears…

I think that public awareness about this problem should be more discussed especially in rural areas…