Category: Uncategorized

Klimaproblematikkens handlingslammelse

Advarsel! Her følger nok en oppramsing om hvor elendig tilstanden på Jorda er på grunn av menneskelig aktivitet. Globale menneskeskapte klimaendringer, store landskapsforandringer og storstilt forurensing av naturen som angivelig skal føre til den sjette store utryddelsen av arter. Den antropocene tidsepoke der mennesket er hovedårsaken til endringer på jorda, menneskets tidsepoke. Smak litt på de ordene. Hva gjør de med deg? Blir du optimistisk? Jeg blir ikke det…

Det er vel ingen tvil om at vi mennesker har en utbredt negativ virkning på jordoverflaten og habitatet vi er så avhengige av (4). Monokulturell matproduksjon, bruk av fossilt brensel og avskoging er noen få eksempler på hvordan vi utnytter naturlige ressurser og ødelegger de i samme slengen (1, 2). Noen forskere (7, 9) påstår at vi har en så stor negativ påvirkning på jorda at vi kan kalle epoken vi lever i, «menneskets tidsalder». Om vår påvirkning er større enn naturen selv, skal jeg ikke diskutere her. Jeg vil istedet rette fokuset over på hva gjentatte advarsler og dommedagsprofetier om klimarelaterte globale endringer kan gjøre med oss.

Det går rett og slett inflasjon i alt «maset» om klima- og naturproblemene.

De fleste nyhetsreportasjer omtaler klimaendringer med bruk av ordene katastrofe og usikkerhet (6) som kan gi saken et svært negativt bilde og som kan føre til følelsen av avmakt (5, 8). Ikke bare språkbruken rundt klimaproblematikken kan virke overveldende, men også selve innholdet i klimabeskjedene. Per Espen Stoknes forklarer i sin bok «What we think about when we try not to think about global warming- Toward a new psycology of climate action» at vi ikke er skapt til å kunne forholde oss til så store og «fjerne» saker som globale klimaendringer. Jo flere fakta vi får tredd nedover ørene om verdens tilstand, desto mer handlingslammet og deprimerte blir vi, noe Stoknes referer til som «et klimaparadoks». Det går rett og slett inflasjon i alt «maset» om klima- og naturproblemene. Spesielt i rike, industrialiserte land bekymrer vi oss mindre og mindre om klimaendringer (3) (men heldigvis bryr vi oss mer om miljørelatert problematikk). Et annen side ved klimaparadokset er at færre og færre tror på at klimaendringer er menneskeskapte. Til tross for at 98% av verdens forskere viser til forskning som påviser realiteten av menneskeskapte klimaendringer, er 50% av verdens befolkning klimaskeptikere. Flesteparten av skeptikerne kommer fra rike, industrialiserte land og Norge er et av dem (3, 8).

Ved å prøve å løse klimaproblemer individuelt, økes følelsen av hjelpeløshet og dårlig samvittighet. Derfor må samholdet i det globale samfunnet styrkes.

I følge Stoknes finnes det minst fem psykologiske barrierer som hindrer oss i å innse alvoret i globale klimaendringer og innføre klimatiltak (8). Disse er avstand, undergang, dissonans, fornektelse og identitet. Ved å redusere viktigheten av egne handlinger, legge til holdninger som passer med egne mangel på tiltak, kompensere for sine klimahandlinger med de få tiltakene man allerede gjør, eller å benekte at problemet eksisterer, klarer man lettere å forholde seg til det reelle problemet som er så alt for skremmende og overveldende for mennesket å ta inn over seg.

Fem psykologiske barrierer som hindrer oss i anerkjenne realiteten i klimaendringer og dermed å utøve klimatiltak

Avstand Vi kan ikke se klimaendringer, de opptrer langt vekke både i rom og tid.

Undergang Vi vil helst unngå temaet fordi det er ubehagelig å tenke på konsekvensene av klimaendringer

Dissonans Dersom vi vet at våre handlinger kan føre til klimaendringer prøver vi å forminske problemet for å unngå konflikt mellom fakta og handling. Det samme gjelder dersom egne meninger er i konflikt med meningene til personer i vår omgangskrets.

Fornektelse Er et forsvar på å unngå frykt for konsekvenser og dårlig samvittighet for at man ikke endrer handlingsmønster.

Identitet Kulturell tilhørighet stiller ofte sterkere enn fakta og vitenskapelig overbevisning

(Kilde: Stoknes, 2014)

Så hva skal vi gjøre da, når vi trenger informasjon, forståelse og fakta på bordet for å ta noen steg i riktig retning for å forhindre ytterligere naturødeleggelser og globale menneskeskapte klimaendringer og fakta bare gjør oss mer distansert fra problemene? Skal vi fortsette som vanlig, eller skal vi prøve å tenke nytt? Stoknes kommer heldigvis med et forslag på hvordan vi kan løsrive oss fra avmakten. Først og fremst kan vi følge tre enkle prinsipper som å snu barrierene på hodet, holde oss til positive strategier og oppføre oss som sosiale innbyggere av planeten, ikke bare som individer. Ved å prøve å løse klimaproblemer individuelt, økes bare hjelpeløsheten og den dårlige samvittigheten, derfor må samholdet i det globale samfunnet styrkes, noe du kan lese mer om her. Stoknes presenterer fem alternative strategier for å kommunisere klimaproblematikken av en mer oppløftende og engasjerende karakter (8).

Fem strategier for å redusere de psykologiske barrierer og øke handlingskraft og positivisme rundt klimatiltak

Sosial strategi å benytte seg av sosiale medier

Støttende strategi Skaper positive følelser angående klimaproblematikk

Forenkling Gjør klimavennlig oppførsel lettvint og tilgjengelig

Fortellerbasert strategi Å bruke fortellerkraft for å lage mening og samhold

Signaler Å bruke indikatorer som gir tilbakemelding på sosial respons

(Kilde: Stoknes, 2014)

Jeg skal ikke inngående forklare hva disse fem strategiene innebærer. I stedet vil jeg oppfordre til å stikke innom biblioteket og lese Stoknes bok, «What we think about when we try not to think about global warming- Toward a new psycology of climate action», (spesielt om du driver med eller formidler klimarelatert forsking). God lesning!

PS! Om Stoknes har rett i det han sier blir opp til fremtiden (og kanskje deg, meg og oss) å avgjøre.

Referanser

- Henriksen S og Hilmo O (2015), Påvirkningsfatorer. Norsk Rødliste for arter 2015. Arstdatabanken <http://data.artsdatabanken.no/Rodliste/Pavirkningsfaktorer> nedlastet 17.03.2016.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), 2005. Living beyond our Means- Natural Assets and Human Well- Being. <http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/pdf/ma_board_final_statement.pdf> nedlastet 17.03.2014

- Nielsen Company. Sustainability Survey: Global Warming Cools Off as Top Concern. Nielsen Press Room, 28.08. 2011. <http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/press-room/2011/global-warming-cools-off-as-top-concern.html> nedlastet 17.03.2014

- Oldfield, F., 2005: Environmental Change- Key Issues and Alternative Approaches, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Painter, J., 2013. Climate change in the media- Reporting Risk and Uncertainty, 2013 B.Tauris & Co., London.

- Reuters Institute for the study of Journalism, 2013. Most News Reports about Climate change Focused on “Disaster” or “Uncertainty”, 16.09.2013. <https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/study-most-news-reports-about-climate-change-focused-%E2%80%98disaster%E2%80%99-or-%E2%80%98uncertainty%E2%80%99>, nedlastet 17.03.2014

- Steffen, W., Crutzen, P.J., McNeil, J.R. 2007: The Anthropocene: Are humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature, Ambio 8, 614-621.

- Stoknes, P. E., 2015. What we think about when we try not to think about global warming- Toward a new psychology of climate action, Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Zalasiewicz, J. and Williams, M., 2008. Are we now living in the Antropocene?, GSA Today, vol.18, 4-8.

Verdas befolkning aukar – vi treng meir mat!

Ei av dei største framtidige utfordringane i verda er korleis vi skal klare å produsere nok mat for den aukande befolkninga i verda. Befolkninga i verda aukar så mykje at det er forventa at vi blir 9 milliardar menneske rundt midten av det 21. århundre (1,2). Dette vil med tida medføre eit høgare trykk på både terrestrisk og marin produksjon av mat, som fører til Allereie i dag fins det mange menneske som er svoltne (1), og med ei auke i befolkning blir dette eit enda større problem. Derfor står følgande utfordringar for tur: auke produksjon av mat på ein måte som er berekraftig og miljøvennleg, og sørge for at dei fattigaste menneska i verda ikkje lenger er svoltne (3). Løysinga på dette problemet er ikkje særleg lett, men i mine auger kan alle prøve å bidra litt. Eg vil sjå på to ulike ting som ”mannen i gata” kan gjere noko med for å hjelpe til, nemlig avfallshandtering og livet som ”fleksitarianar».

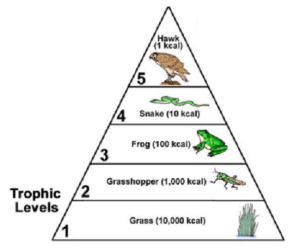

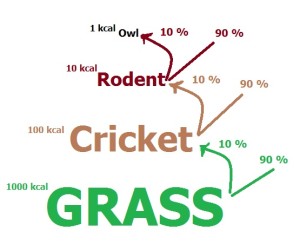

Før eg skal sjå nærmare på dette, må eg forklare litt kva trofiske nivå går ut på. Dei ulike nivåa i ei næringskjede, blir kalla trofiske nivå (sjå figuren ovanfor). I dei nederste trofiske nivåa har vi produsentane som nyttar solenergi for fotosyntese. Vidare oppover i nivåa har vi konsumentar som et produsentane. Mellom kvart nivå i næringskjeda blir 10% nytta til å produsere ny biomasse, noko som vil seie at dei resterande 90% ikkje blir utnytta. Dette gjeld begge dei to hovudområda vi hentar og produserer mat frå; det marine systemet, altså havet og det terrestriske systemet, altså jordbruk.

Avfallshandtering

Rundt 30-40% av all mat som blir produsert blir ikkje nytta av ulike grunnar (1). Dette gjeld både for vestlege land som Norge, og land som er i utvikling, som for eksempel i Sør-Aust Asia. Forskjellen ligg i kvar maten blir øydelagd. I ulike delar av Asia blir mykje av maten øydelagd på grunn av manglande standard på transport eller oppbevaringsfasilitetar, og av skadedyr som øydelegg avlingane (1). I vestlege land som er kome langt i utviklinga, som for eksempel Norge, er det heilt andre årsakar til at maten blir øydelagd eller kasta. Transport og oppbevaringsmoglegheitene er gode nok til at mat ikkje blir øydelagd på same måten som i land som er i utvikling. Her i landet er det mykje mat som blir kasta av kosmetiske grunnar, der maten aldri når butikken fordi den ikkje er stor nok eller at forma ikkje er rett (1). Vidare er mat relativt billig, noko som gjer tilgangen på mat større og … I tillegg er best før-datoane ofte satt tidlegare enn dei treng å ver satt, fordi dei ulike merka som produserer og sel denne maten vil sørge for kvalitet på sin mat.

Forbetringar i infrastrukturen til transportsystemet i mindre utvikla land, kan hjelpe til med å redusere mengda mat som blir øydelagd (1). Behovet for vidare forsking i lagring etter hausting er også tilstades, og kan vere ein måte å redusere avfall.

Dersom vi prøvar å kaste mindre mat, vil forbruket vårt minke. Då vil butikkane ta inn mindre mat, og matproduksjonen minke. Dette vil igjen føre til at arealet som blir brukt for matproduksjon, ikkje vil ha like høgt trykk, og vi kan utnytte det betre etter kvart når befolkninga aukar. Auking i prisen på mat kan også føre til nedgang i avfall (1). Ein anna måte å redusere avfall på er bevisstgjering av dette problemet, og med dette etablering av ein anna tenkemåte når det gjeld matavfall (1).

”Livet som fleksitarianar”

Ca. 80% av alt land som blir brukt av menneske, blir brukt til produksjon av mat (4). Som nemnt tidlegare ved trofiske nivå, krevjast det veldig mykje energi for å produsere mat som er i høgare trofiske nivå, som kjøtt. For eksempel, dersom ein primærprodusent produserer 1000 kcal, og vi haustar mat i tre trofiske nivå over primærprodusenten vil utbyttet berre vere 1 kcal. Dermed vil det vere ein stor fordel å hauste meir i lågare trofiske nivå for å få eit større utbytte når det no er og etter kvart blir eit aukande behov for dette. Heldigvis ser ein ei auking i menneske som vel å vere vegetarianarar, anten på heiltid eller deltid. Sjølvsagt treng ikkje alle å bli vegetarianarar, men om mange vel vekk kjøtt berre ein eller to dagar i veka, vil dette utgjer ein stor forskjell. ”Deltids-vegetarianarar” har no og fått eit nytt begrep: fleksitarianarar, som beskriv personar som vel bort kjøtt, fisk, melk og egg når dei kan og vil (4). Dette kan vere eit enkelt, men viktig grep som mange kan ta for å få produsert meir mat i framtida.

Dette gjeld også i havet, der vi i veldig stor grad haustar i høge trofiske nivå i dag, som for eksempel torsk. I dag blir det og praktisert selektiv fisking av fiskar med rett storleik, der små fisk ofte blir kasta ut att i sjøen. Dersom denne praksisen blir vidareført, vil dette føre til overfiske i framtida. Derfor bør det og vere eit mål hauste i lågare trofiske nivå også i havet. Balansert hausting i havet, der det fins utrulege mengder primærprodusentar. Dersom vi innfører ein slik praksis i staden, vil det gi oss mykje meir mat (om vi klarar å utnytte dei mikroskopiske organismane i havet), i tillegg til at det vil hjelpe til å bevare marine bestandar.

Oppsummert vil eg peike på at alle kan bidra litt, om det er ein kjøttfri tysdag, eller redusering av avfall. Dette er enkle grep som dei fleste klarar å gjennomføre.

Referanser:

- Godfray H.C.J., J. R. Beddington, I.R. Crute, L. Haddad, D. Lawrence, J.F. Muir, J. Pretty, S. Robinson, S. M. Thomas, C. Toulmin (2010) Food: Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science. 327: 812-818

- Duarte, C. M., Holmer, M., Olsen, Y., Soto, D., Marba, N. Guiu, J., Black, K. & Karakassis, 1. (2009). Will the oceans help feed humanity?

- Von Braun, J. (2007). The World Food situation: New Driving Forces and Required Actions. Washington: International Food Policy Research Insitute.

- Stehfest, E., Bouwman, L., van Vurren, D.P., den Elzen, M. G. J., Eickhout & B. Kabat, P. (2009) Climate benefits of changing diet. Climate change.

- Ertesvåg, F. (2016). Veggiser i voldsom vekst: nå kommer fleksitarianerne. VG. 25. Februar. Henta frå: http://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/godt-no/veggiser-i-voldsom-vekst-naa-kommer-fleksitarianerne/a/23625195/ (23.02.16)

- Skern-Mauritzen, M., Howell, D., Hansen, C., Bjordal Å., og Huse, G. (2015). Barentshavet – for stort og komplisert for en strikt balansert høsting. Henta frå: http://www.imr.no/filarkiv/2015/03/barentsh_balansert_hosting_raudate.pdf/nb-no (25.02.16).

Skrive av: Anne Marte Fauske

Save biodiversity for humanity.

(For the sake of argument)

By Erlend Bersaas.

Increasing temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, loss of ice, rising sea levels, loss of biodiversity, “the sixth extinction”, freshwater shortage, ocean acidification. All apparently due to one single species astonishing evolutionary success. Homo sapiens sapiens. Humans.

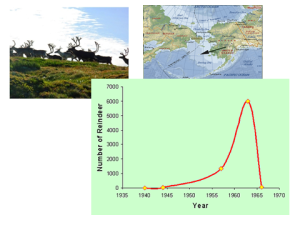

The impact our species have had is so vast that we are in the process of defining our own epoch. The Anthropocene (Vaughan, 2016). The ongoing debate on when the Anthropocene started is not that interesting. The point is that it already has started, and we need to slow down the destruction of our habitat. If not, we are dangerously close to reaching our species carrying capacity. Just feeding an ever-increasing population will eventually become difficult should there not come a second “green revolution” (Godfray et al. 2010). We do not want to end up like the reindeers of St. Matthews Island, an island in the Bering Sea, where 29 animals were introduced in 1944, increased to over 6000, with the result of total collapse by 1966 (Klein 1968).

Hardly any place on the planet is unaffected by humans (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005). Some honourable mentions could be the lakes, which we have not yet disturbed; beneath the cryosphere, but the rest of the planet have experienced some form of human fingerprint. Most of the implications of our behaviour is negative for other species although there are of course exceptions, such as rats and maize, or sheep for that matter, but in general, I do not think too many will disagree with the idea of humans as a negative force on the wildlife and ecosystems. As the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) states:

Human actions are fundamentally, and to a significant extent irreversibly, changing the diversity of life on Earth, and most of these changes represent a loss of biodiversity. Changes in important components of biological diversity were more rapid in the past 50 years than at any time in human history. Projections and scenarios indicate that these rates will continue, or accelerate, in the future. (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, p. 2)

However, why is this a bad thing? Sure, we have transformed a lot of the planet, but in doing so we have become greatly successful. And basically that is what it`s all about.

We are after all competing with every other organism on this planet. The problems arise when we have exhausted our recourses and begin to suffer for it. Thinking that nature is some pristine place, an Eden, where animals and plants live in some sort of stabile harmony, is not going to get us anywhere. We are here, and we are a part of nature as is every other organism. We just dominate everything. We have even made up stories to alleviate us from any moral dilemma concerning other species. The only implications we have had to consider was the one that affected us directly. Just think of what The Bible is saying on the matter of human supremacy on nature:

And God blessed Noah and his sons and said to them, «Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth. The fear of you and the terror of you will be on every beast of the earth and on every bird of the sky; with everything that creeps on the ground, and all the fish of the sea, into your hand they are given. Every moving thing that is alive shall be food for you; I give all to you, as I gave the green plant.”

Genesis 9. 1-3 (God, no date.)

The meme of humans as something outside of nature seems to have been greatly successful and have probably participated in our species great evolutionary success. However, because we no longer had to take considerations to what we did with nature, more or less every other organism suffered*.We can argue that this is morally wrong, and that everything has an intrinsic value. It does however look like self-preservation is the underlying argument when trying to convince anyone to save biodiversity and ecosystems.

The UN gives us the argument that we have to save biodiversity because “Biodiversity produces six major services for us: It gives us clean water, food, building materials and medicines. It protects us against extreme weather and help prevent climate change” (Globalis 2016 (my translation)). We can also add different pleasures as recreation, beauty and knowing that some organisms exist, but we should be honest about it. We want to protect life in all its forms due to its value for us. If we do not think anthropocentrically we know what we have to do to stop our domination and destruction of other species, but I for one will not participate in culling half the world’s population.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand. (Sagan 1994)

*Without going into whether every organism can suffer, because that will only lead to some sort of philosophical argument of where different organisms should be placed on a gradient for the separation of humans from the rest.

Figures:

1: Piraro, D (2007) [Internet] available at: http://bizarro.com/page/2/?s=evolution&submit=Search . Accessed [26.02.2016]

2: Klein, D., Walsh, J. and Shulski, M. (2009) What Killed the Reindeer of Saint Matthew Island? [Internet] available at: http://www.weatherwise.org/Archives/Back Issues/2009/Nov-Dec 2009/full-Reindeer.html. Graph from: [ Internet]http://qualicuminstitute.ca/tenets/317-2/ . Accessed [25.02.2016]

3: Hardin (No Date) [Internet] available at: http://thechive.com/2009/02/26/every-single-evolution-cartoon-we-could-get-our-hands-on-36-photos/ . Accessed [26.02.2016]

4: NASA (2015) Blue Marble – Image of the Earth from Apollo 17. [Internet] http://www.nasa.gov/content/blue-marble-image-of-the-earth-from-apollo-17 . Accessed [26.02.2016]

Sources:

Globalis (2016) Hvorfor er naturmangfold viktig? [Internet] http://www.globalis.no/Tema/Naturmangfold/2.-Hvorfor-er-naturmangfold-viktig .Accessed [25.02.2016]

God (No Date) The Bible. Nicaea.

Godfray H.C.J., J. R. Beddington, I.R. Crute, L. Haddad, D. Lawrence, J.F. Muir, J. Pretty, S.

Robinson, S. M. Thomas, C. Toulmin (2010) “Food: Security: The Challenge of

Feeding 9 Billion People”. Science. 327: 812-818

Klein, D. R. (1968) The introduction, increase, and crash of reindeer on St. Matthew Island.

- Wildl. Manage. 32: 351-367.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

Sagan, C. (1994) Pale blue dot. Also available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PN5JJDh78I

Vaughan, A (2016) Human impact has pushed Earth into the Anthropocene, scientists say. The Guardian. [Internet] http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jan/07/human-impact-has-pushed-earth-into-the-anthropocene-scientists-say . Accessed [25.02.2016]

An Argument for Managing the World’s Meat Consumption

Some of the greatest concerns of our time is the overuse of resources, global warming and the great increase in the human population. In spite of that 50% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface is used for crop-production and grazing areas (Kareiva et al. 2007) we will not be able to feed our soon to be 9 billion people ( Godfray et al. 2010). In addition to this, it is in human interest to reduce the land used for agriculture due to exhaustion and conservation of areas. It is important that we start using our resources more efficiently, and in a more sustainable way before it is too late.

Around 30% of the Earth’s surface, or 80% of all land used by humans, is used to support livestock for meat production (Stehfest et al. 2009). A big part of this could be used to create food on a lower tropical level, which means more energy (food) on the same amount of area, which could in turn feed more people. Only about 10 percent of the energy stored in the primary producers (greens) is transferred to the consumer. Not to forget- meat production is one of our biggest climate concerns, because of emissions from livestock of methane, nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide, and stands for around 18% of our total greenhouse gas emissions (Stehfest et al. 2009).

To be able to reach a more sustainable way of agriculture, we do not only need a to change the way we do things, but we also need a drastic change in the way the richer part of the world thinks about food (Walsh, 2013). If we were forced to cut down our consumption of meat, it could have major effects on reducing the rate of the global warming, we could sustain the population growth, at least for some time, not to mention the effect it could have on our private health. A more balanced diet than what you often find in the western world today will be economically positive, where many people have a high fat- and sugary diet, and their health issues cost the state a lot of money (Godfray et al. 2010).

This does not mean that we should quit all husbandry and meat production, and that we all should be vegetarians. Meat and other animal products is an important source of proteins and nutrients. In addition, parts of the human livestock are grazing animals who use landscape that could not be used for crop production anyway (Godfray et al. 2010). But it means that it’s time to realize that our earth, which is the only earth we will ever have, needs us to start thinking more long-term, and start using our land so that it can keep feeding us for the years to come. It needs us to realize that we cannot keep consuming in this way, when there is not enough food for the rest of the world.

For every 100 kg of proteins in ruminant meat, we require 60 m2, while beans, peas, lentils and chickpeas only require 25m2 to create the same amount of proteins (Stehfest et al. 2009). This means that we could sustain over twice as many people in proteins by a change in land use. And according to PETA’s (People for the ethical treatment of animals) website, as of February 2016; it takes about 20 times as much land to support a meaty diet, than a fully plant based diet.

The average American eats 122 kg of meat per year; this is 334 grams a day, or 2.3 kg a week (Walsh, 2013). For comparison, the average Norwegian eats 65.4 kg a year (Barclay, 2014), which is just above half the American consumption. The country to score highest on meat consumption per person is Luxembourg with as much as 301.7 kg of meat per year, which equals to 375 grams a day. This is a ridiculous amount of meat, and this amount of beef requires 75m2 of land use per person each day of the year (Barclay, 2014). Of course, the amount of meat is shared between poultry, pork, beef and other meat, where beef requires the biggest amount of land.

Having a meat consumption that would be devastating for the world if adopted by other nations, should be reason enough to manage the meat-culture down to sustainable levels. It is to be expected that developmental countries to increase their meat consumption as they become wealthier (Begon et al. 2014). Reducing the American, and other first world countries’ meat consumption to the levels of India (3.2 kg a year), or Bangladesh (3.6 kg a year) (Barclay, 2014) seems unrealistic, but to reduce it by some, (or even half) should be possible. In fact a declaration called the “Barsac Declaration” were put forth by a group of biologist in 2009, saying that no-one should get more that 35- 40% of their protein from meat, which would reduce the American and other first world countries’ consumption of meat by half. Not only would this do the world so much good in the means of emissions, and the amount of food, but it is also the upper limit recommendation in a healthy diet. (Begon et al. 2014).

By Åsne Brede

References

Kareiva P., S. Watts, R. McDonald, T. Boucher (2007) “ Domesticated Nature: Shaping Landscapes end Ecosystems for Human Welfare” Science 316: 1866-1869.

Stehfest E., L. Bouwman, D.P. van Vurren, M.G.J. den Elzen, B. Eickhout, P.Kabat (2009)

“Climate benefits of changing diet”. Climatic Change. 95:83-102

Godfray H.C.J., J. R. Beddington, I.R. Crute, L. Haddad, D. Lawrence, J.F. Muir, J. Pretty, S.

Robinson, S. M. Thomas, C. Toulmin (2010) “Food: Security: The Challenge of

Feeding 9 Billion People”. Science. 327: 812-818

Walsh B. (2013) “The Triple Whopper Environmental Impact of Global Meat Production”. TIME. Available: http://science.time.com/2013/12/16/the-triple-whopper-environmental-impact-of-global-meat-production. Last accessed 23/02/16

Barclay E. (2014) “A Nation Of Meat Eaters: See How It All Adds Up“. The Salt. Available: http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2012/06/27/155527365/visualizing-a-nation-of-meat-eaters. Last accessed 24/02/16

Begon M., R.W. Howarth, C. R. Townsend. (2014). The ecology of human population growth, disease, and food supply. United States of America: Wiley. p. 406- 440

PETA “Meat and the environment” Available: http://www.peta.org/issues/animals-used-for-food/meat-environment/ Last accessed 25/02/16

Image taken from www.freeimages.com

The sixth mass extinction

By: Ragnhild Gya

Whether we are going into the sixth mass extinction or not has been heavily debated. In 2015 a paper was published by Gerardo Ceballos and his colleagues were they state that the sixth mass extinction is happening, and that we are causing it. I am now going to try and explain their arguments the best I can, you can also read the article yourself (reference in the end of this blog entry).

Extinctions happen all the time. Did you know that over 90 % (and maybe closer to 98%) of all species that has lived on Earth is now extinct? Whether we have a net gain or a net loss of biodiversity and species depends on the rate of occurring new species and the rate of extinctions. This “normal” amount of species going extinct is called the background rate of extinctions. This background rate stands for most of the extinctions in the history of the earth; actually the mass extinctions can only be blamed for 4 % of all extinctions in the last 600 million years.

When the extinction rate is much higher than the background rate, it is classified as a mass extinction. The most famous one is the one that killed the dinosaurs, 65 million years ago, which is called the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. The one that killed the most species is the Permian-Triassic extinction event, which made 95 % of marine species and 70 % of species on land go extinct. Are we also now in a period similar to these two?

To figure this out scientist estimate the normal background rate of extinctions from fossil records, written observations etc. and compare that to a number that they have calculated for our current extinction rate. A lot of scientists have published papers where they conclude that we are in a mass extinction because of the results of these calculations. Ceballos and his colleagues discussed the fact that the background rates were calculated from marine invertebrates and that the background rate would probably be higher if we considered other groups as well. So instead of using the most used background rates which are between 0.1 and 1 extinction per 10 000 species per 100 years (0.1-1 E/MSY), they used 2 E/MSY. They more than doubled the previous number for the background rate, which should make it harder to get a result that says that we are in the sixth mass extinction if we actually are not.

To find the modern extinction rate, the used the IUCNs (International Union of Conservation of Nature) list over threatened and extinct species. They have three “extinct” categories: “extinct” (EX), “extinct in the wild” (EW) and “possibly extinct” (PE). They calculated using two different approaches: the highly conservative one with only using numbers from the category extinct, and the conservative one using all three categories.

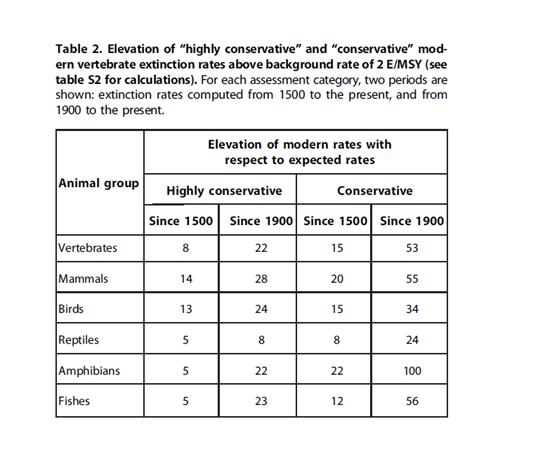

You can see the results of these calculations in the table underneath. The numbers are how much higher the current extinction rate is compared to the background rate. As you can see, it varies from 8 to 100, and this is using the conservative method to calculate it. As a conclusion we are now no longer in doubt about this period – it is the sixth mass extinction.

Table: Ceballos et al. (2015)

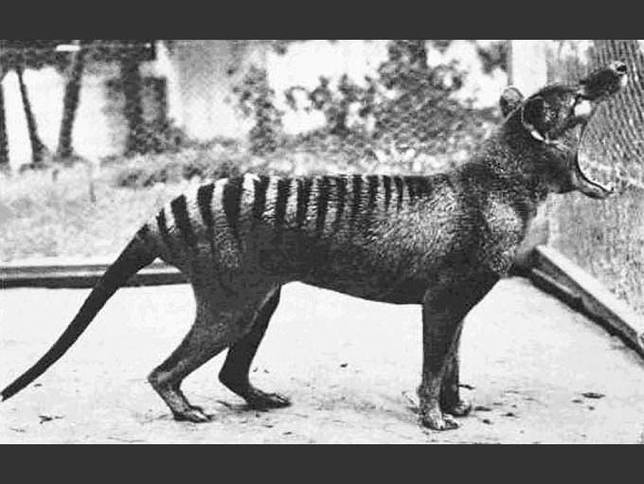

Just to remind you what we are losing, here are some species that have gone extinct in the past 100 years:

Extinction 1: The last Thylacine in captivity, pictured above, died in 1936.

Extinction 2: Wester Black Rhino. Once widespread in central west Africa, in 2011 it was declared extinct.

Extinction 3: Golden Toad. Only described to science in 1966, and once abundant in a 30 square mile area of the cloud forest above Monteverde, Costa Rica, none of the toads have been sighted since the 15th of May 1989

References

Kevin J. Gaston and John I. Spicer (2004). Biodiversity – an introduction. 2nd ed. : Blackwell Publishing. p19-48.

Gerardo Ceballos, P. R. Ehrlichm A. D. Barnosky, A. García, R. M. Pringle, T. M. Palmer. (2015). Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Science. 1 (5), .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extinction_event (24/02/2016)

Pictures:

http://www.treehugger.com/slideshows/natural-sciences/glimpse-what-we-lost-10-extinct-animals-photos/ (24/02/2016)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/martijnmunneke/6521931525/sizes/l/in/photostream/ (24/02/2016)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bufo_periglenes2.jpg (24/02/2016)

Predicting the consequences of human impact a changing biosphere, implications of the lack of species knowledge.

by Trond R. Oskars

Many species and Biodiversity (1) as a whole is currently under a lot of pressure, not only climate change (2, 3, 4), but also increased direct interference by humans (5, 6, 7, 8, 9). This may lead to extinction events, severe shifts in species interactions and ecosystem composition (10, 11, 12). Due to this assessing current and past biodiversity and understanding their interactions and responses to stressors have become more important to try to predict the outcome of the ongoing human driven change of the biosphere (13, 14).

It is a known problem that there are large gaps in the fossil record (14), the older the rocks the bigger the chance that older fossils will not survive to be discovered and cannot be expected to match the diversity represented in more recent fossil assemblages (14, 15, 16). However the fossil record can still tell us a lot about long time stability of organism groups and ecosystems (14, 16), thus gives us the board picture of the effect of stressors comparable to human actions. However for a more detailed view we need data from living species (14).

Here we encounter an additional problem the lack of knowledge of extant species of many groups. About 1.2 to 1.9 million species have been formally described and given a name (17, 18). The number of species that currently exist in the world (not counting bacteria and their kin) varies by the method used, but is has been estimated as high as 8.7 million (18, 19). This leaves the majority (over 80%) of all species unknown or unnamed (20).

This opens for the possibility that species may fail to be recognized, discovered or described before being driven to extinction (13, 18). Even for relatively well known ecosystems (tropical forests) and well-studied animals (vertebrates; amphibians) there are likely still undiscovered species (18, 21, 22, 23, 24). This means that the number of undescribed species may be even higher for unexplored or inaccessible areas or taxa[1].

This also means that we in most cases know little about their roles in the ecosystem, how they interact with other species, and how the extinction may affect the ecosystem as whole.

Describing species takes a long time, averagely 21 years! (20). Much due to the shortage of taxonomists and that most species are rare and only represented by single specimens, leading to many researchers waiting until they have more specimens available[2] (20, 25). Museum collections are reservoirs of many undescribed species, sampled in bulk on long ago expeditions and many of which may already be extinct (20). Another factor is that most taxonomists don’t live in developing countries where Biodiversity is highest (20, 26). Many species can also be relatively well known by those who do live there (23), but have never been formally described or studied in other contexts. If no one has studied a species, how can we know if it is a common, widespread species or a group of similar endemic species? This is especially problematic in cases where their most well-known quality is that they are especially tasty with soy sauce (27*[3]).

There is an additional dimension to this, what about the already described species? Does everybody agree on what a species is? (This is even further complicated by species concepts).

The problem is how we define what a species is, the method used, and the disagreement between these. Many taxonomists and sytematicists rely either on morphology or DNA to define species. Either they don’t trust one method, or they don’t have a choice, like paleontologists (28) or those researching cryptic species[4] (29).

However, In some cases convergent evolution[5] can make unrelated taxa that have some habits or habitats in common to seem closely related by morphology (30, 31) or populations that seem identical may in fact be evolutionary distinct (32) This may lead to conflict between methods and lead to bad taxonomy in the form of wrongful synonyms[6] (many taxa lumped into one) or undiscovered synonyms (one taxa counted as several). Mora et al. (18) asked 2938 taxonomists about what they felt could limit taxonomic effort[7], most answered synonyms as a major problem on the species level even if did not affect higher taxonomic levels drastically. So likely the general trends in taxa response to stressors can be trusted, but on the species level this resolution may be lacking.

How to define speices can wary form disiplines to the methods used within the disiplines.

This can be highly problematic in conservation of Biodiversity and ecosystem services. A study by Prie et al. (33) on the freshwater clams Unio in Europe, found three distinct species and several distinct sub species based on DNA. This group is riddled with synonyms based on morphology, which has impacted the conservation status of the species, leading to some of the groups to be isolated and population reduced due to human activities (33).

This lack of knowledge is dangerous as it reduces our ability to conserve species or communities that may be potentially important for ecosystem function (24, 33, 34, 35). Additionally, if enough species are not properly recognized we cannot see the complete picture of biodiversity patterns or estimate extinction rates (21, 24). It also makes it difficult to transform the scientific data into information that can be used by legislators who decide on conservation and the people who actually live alongside the species (however some manage *).

We stand to lose important ecosystem processes and services that may in turn harm other species, or even come to affect human populations (21, 34, 36, 37). Basically we don’t really know what we have lost until it is gone. Due to this it would beneficial not only to protect areas that we know to be especially biodiverse, but also areas that are relatively unexplored or less disturbed by humans, as there are likely a high diversity of undescribed species there (24).

References

- Wilson, E. O. (1988). The current state of biological diversity. In Biodiversity, E.O. Wilson & F.M. Peters, (Eds). 3-18 PP. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Accessed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219273/ at 20.02.16

- Walther, G. R., Post, E., Convey, P., Menzel, A., Parmesan, C., Beebee, T. J., et al., & Bairlein, F. (2002). Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature, 416(6879), 389-395.

- Walther, G. R. (2010). Community and ecosystem responses to recent climate change. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 365(1549), 2019-2024.

- Parmesan, C. (2006). Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 637-669.

- Alongi, D. M. (2002). Present state and future of the world’s mangrove forests. Environmental conservation, 29(03), 331-349.

- Stuart, S. N., Chanson, J. S., Cox, N. A., Young, B. E., Rodrigues, A. S., Fischman, D. L., & Waller, R. W. (2004). Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science, 306(5702), 1783-1786.

- Brook, B. W., Sodhi, N. S., & Bradshaw, C. J. (2008). Synergies among extinction drivers under global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23(8), 453-460

- Butchart, S. H., Walpole, M., Collen, B., Van Strien, A., Scharlemann, J. P., Almond, R. E, et al. & Carpenter, K. E. (2010). Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science, 328(5982), 1164-1168.

- Polidoro, B. A., Carpenter, K. E., Collins, L., Duke, N. C., Ellison, A. M., Ellison, J. C., et al. & Livingstone, S. R. (2010). The loss of species: mangrove extinction risk and geographic areas of global concern. PloS one, 5(4), e10095.

- Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J., & Melillo, J. M. (1997). Human domination of Earth’s ecosystems. Science, 277(5325), 494-499.

- Chapin III, F. S., Zavaleta, E. S., Eviner, V. T., Naylor, R. L., Vitousek, P. M., Reynolds, H. L., et al. & Mack, M. C. (2000). Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature, 405(6783), 234-242.

- Van der Putten, W. H., Macel, M., & Visser, M. E. (2010). Predicting species distribution and abundance responses to climate change: why it is essential to include biotic interactions across trophic levels. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 365(1549), 2025-2034.

- Stork, N. E. (1993). How many species are there?. Biodiversity & Conservation, 2(3), 215-232.

- Blois, J. L., Zarnetske, P. L., Fitzpatrick, M. C., & Finnegan, S. (2013). Climate change and the past, present, and future of biotic interactions. Science, 341(6145), 499-504.

- Raup, D. M. Taxonomic diversity during the Phanerozoic. Science 177, 1065–1071 (1972).

- Benton, M. J., Wills, M. A., & Hitchin, R. (2000). Quality of the fossil record through time. Nature, 403(6769), 534-537.

- Chapman, A. D. Numbers of living species in Australia and the world. (2009): 1-78 PP. Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study. Canberra, Australia. Available form https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/2ee3f4a1-f130-465b-9c7a-79373680a067/files/nlsaw-2nd-complete.pdf accessed on 20.02.16.

- Mora, C., Tittensor, D. P., Adl, S., Simpson, A. G., & Worm, B. (2011). How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean?. PLoS Biol, 9(8), e1001127.

- May, R. M. (2011). Why worry about how many species and their loss?. PLoS Biol, 9(8), e1001130.

- Fontaine, B., Perrard, A., & Bouchet, P. (2012). 21 years of shelf life between discovery and description of new species. Current Biology, 22(22), R943-R944.

- Ceballos, G., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2009). Discoveries of new mammal species and their implications for conservation and ecosystem services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(10), 3841-3846.

- Geissmann, T., Lwin, N., Aung, S. S., Aung, T. N., Aung, Z. M., Hla, T. H., Grindley, M., Momberg, F. (2011). A new species of snub‐nosed monkey, Genus Rhinopithecus Milne‐Edwards, 1872 (Primates, Colobinae), from northern Kachin State, northeastern Myanmar. American Journal of Primatology, 73(1), 96-107.

- Hart, J. A., Detwiler, K. M., Gilbert, C. C., Burrell, A. S., Fuller, J. L., Emetshu, M., Hart, T. B., Vosper, A., Sargis, E. J, Tosi, A. J. (2012). Lesula: a new species of Cercopithecus monkey endemic to the Democratic Republic of Congo and implications for conservation of Congo’s Central Basin. PLoS One, 7(9), e44271.

- Giam, X., Scheffers, B. R., Sodhi, N. S., Wilcove, D. S., Ceballos, G., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2012). Reservoirs of richness: least disturbed tropical forests are centres of undescribed species diversity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 279(1726), 67-76.

- Lim, G. S., Balke, M., & Meier, R. (2012). Determining species boundaries in a world full of rarity: singletons, species delimitation methods. Systematic biology, 61(1), 165-169.

- Gaston, K. J., May, R. M.(1992). Taxonomy of taxonomists. Nature, 356, 281-282.

- Lim K. K. P., Murphy D. H, Morgany, T., Sivasothi, N.,Ng P. K. L. Soong, B. C.,. Tan, H. T. W, Tan, K. S., Tan, T. K. A (1999) Guide to Mangroves of Singapore Peter K. L. Ng and N. Sivasothi (ed). BP Guide to Nature Series published by the Singapore Science Centre, sponsored by British Petroleum. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, The National University of Singapore & The Singapore Science Centre. Online excerpt: http://mangrove.nus.edu.sg/guidebooks/text/2088.htm accessed on 19.02.16

- Kaiser, G., Watanabe, J., & Johns, M. (2015). A new member of the family Plotopteridae (Aves) from the late Oligocene of British Columbia, Canada. Palaeontologia Electronica, 18(3), 1-18

- Jörger, K. M., & Schrödl, M. (2013). How to describe a cryptic species? Practical challenges of molecular taxonomy. Frontiers in Zoology, 10(1), 1.

- May, R. M. (1990). Taxonomy as destiny. Nature, 347(6289), 129-130.

- Oskars, T. R., Bouchet, P., & Malaquias, M. A. E. (2015). A new phylogeny of the Cephalaspidea (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia) based on expanded taxon sampling and gene markers. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 89, 130-150.

- Hebert, P. D., Penton, E. H., Burns, J. M., Janzen, D. H., & Hallwachs, W. (2004). Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(41), 14812-14817.

- Prié, V., Puillandre, N., & Bouchet, P. (2012). Bad taxonomy can kill: molecular reevaluation of Unio mancus Lamarck, 1819 (Bivalvia: Unionidae) and its accepted subspecies. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, (405), 08.

- Suzán, G., Marcé, E., Giermakowski, J. T., Mills, J. N., Ceballos, G., Ostfeld, R. S., Armien, B,. Pascale, J. M.,Yates, T. L. (2009). Experimental evidence for reduced rodent diversity causing increased hantavirus prevalence. PloS one, 4(5), e5461

- Mace, G. M. (2004). The role of taxonomy in species conservation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 359(1444), 711-719.

- Worm, B., Barbier, E. B., Beaumont, N., Duffy, J. E., Folke, C., Halpern, B. S.,. Jackson J. B. C, Lotze, H. K., Micheli, F., Palumbi, S. R., Sala, E., Selkoe, K. A., Stachowicz, J. J., Watsom, R. (2006). Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science, 314(5800), 787-790.

- Dugan, P. J., Barlow, C., Agostinho, A. A., Baran, E., Cada, G. F., Chen, D., et al. & Marmulla, G. (2010). Fish migration, dams, and loss of ecosystem services in the Mekong basin. Ambio, 39(4), 344-348.

[1] Taxa- A group of individuals or species that due to one or several methods are seen my Taxonomists or sytematicists to form one discernable unit and given a name.

[2] I have more than once spent two whole days dissecting a specimen less than 1 mm long as it was the only one available.

[3] I am revising the taxonomy of this group, current knowledge is next to none.

[4] Cryptic species- A species that is molecular distinct, but more or less impossible to separate form related species based on morphology.

[5] Convergent evolution- When evolution drives two species that are unrelated to gain a similar morphology, for example due to living in a similar habitat, also possible for related, but not closely related species trough parallel evolution.

[6] Synonymy- Basically when one taxa is regarded as the same as another and the most recent name must be replaced by the oldest available name.

[7] Taxonomic effort- Species discovery rates and to some degree the number of taxonomist working on a group (18).

Food for a growing population of humans

Today we have a large population of people who are starving or suffering from malnutrition. According to the food assistance branch of the UN, the World Food Program, 45% of deaths in children under the age of five is caused by poor nutrition. They also state that in the sub-Saharan Africa, which is the region with the highest prevalence of hunger, one in four people are undernourished

As we can see getting enough food for our large human population is already a problem – and it is only going to get worse. The human population is predicted to keep growing up to 9 billion (Godfray et al. 2010).

To understand some of the problems with choosing types of food for a larger human population we need to know a little bit about different trophic levels, which ScienceDaily defines as:

“In ecology, the trophic level is the position that an organism occupies in a food chain – what it eats, and what eats it.”ScienceDaily 11/02/16

In each trophic level the organism is using most of the energy for everyday processes, and that energy is ultimately lost for the ecosystem as respiratory heat. The energy that is not lost is used to build new biomass, which is called the production efficiency. Across all species the average production efficiency is 10 %, which means that the remaining 90 % is lost between each trophic level. These numbers differ between types of organism and especially with what kind of metabolism the organism has. The production efficiency can be anything from 1% to 50%.

Let’s look at one example. 10 % of the energy that the grasses produce during a lifetime is possible to transfer to the next trophic level: a cricket. The growth of the cricket biomass, which is only 10 % of the energy it got from the grass, will be the source of energy for a rodent. 10 % of that energy again will be accumulated in the biomass of the rodent, which the owl will be eating. So if you start out with 1000 kcal of grass, the owl at the top will only end up with 1 kcal of this.

This helps us to understand that if we use a lower trophic level as a source for food, we can get more food for more people and less energy is lost in the food chain.

By simulating the scenario that we eat less meat Stehfest et al. (2009) have found that we could reduce the amount of pasture area with 80 % compared to our dietary habits of today. This means that we could produce more food for more people, but decrease our use of land for food production. Stehfest et al. (2009) also points out that this could have a positive effect on the climate because these former crop-landscapes would capture carbon from the atmosphere as the vegetation grow back.

It looks like one of the ways that we can solve the problem of finding enough food for a growing human population is to reduce our consumption of meat. Are we willing to do that?

Written by: Ragnhild Gya

Sources:

Begon M., R.W. Howarth, C. R. Twonsend. (2014). The flux of energy and matter through

ecosystems. In: Essentials of Ecology. United States of America: Wiley. p 309-340.

Godfray H.C.J., J. R. Beddington, I.R. Crute, L. Haddad, D. Lawrence, J.F. Muir, J. Pretty, S.

Robinson, S. M. Thomas, C. Toulmin (2010) “Food: Security: The Challenge of

Feeding 9 Billion People”. Science. 327: 812-818

ScienceDaily. (2015). Trophic level. Available:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/terms/trophic_level.htm. Last accessed 11/02/16.

Stehfest E., L. Bouwman, D.P. van Vurren, M.G.J. den Elzen, B. Eickhout, P.Kabat (2009)

“Climate benefits of changing diet”. Climatic Change. 95:83-102

World Food Program. (2016). Hunger Statistics. Available: https://www.wfp.org/hunger/stats.

Last accessed 11/02/16.