About Benjamin Robson

View all posts by Benjamin Robson

Differing perceptions on conserving nature

A Tharu village in the buffer zone of Chitwan National Park, Nepal. (photo: Ben Robson)

The natural world has constantly changed and developed as a result of both natural and anthropogenic influences over geological time [1], the notion of conserving and preserving landscapes for future generations is however relatively recent. In particular, a distinction exists between perceptions of how “pristine” landscapes should be conserved between the more developed “Northern” countries and the less developed nations in the “South.”

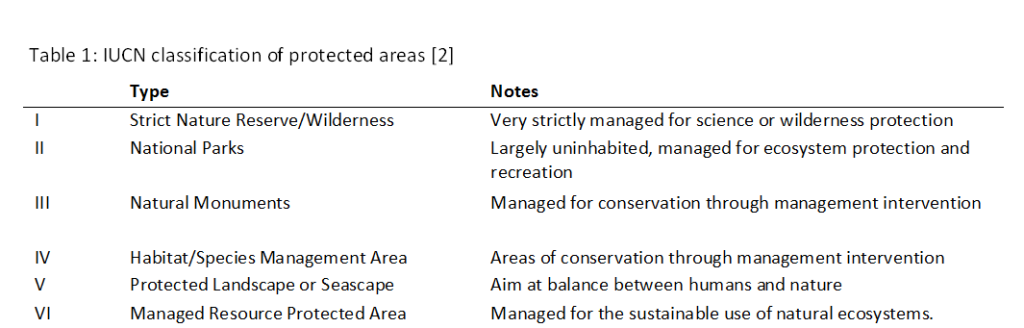

Countries in the North generally moved from a predominantly rural population to a more urbanised population during the industrial revolution, as such when national parks and conservations were established in the mid-20th century, significant populations were already settled within the new national park boundaries, thereby limiting the amount of conservation that could be carried out. National parks in Western Europe generally conform to a grade V classification according to the IUCN classification scheme (table 1), aiming to find a compromise between the needs of both mankind and nature.

75% of land within English and Welsh national parks is privately owned meaning it is seldom that pure «wilderness» is found. Activities such as farming, mineral extraction or power generation are in some cases permitted within the park, but economic activity that that could aesthetically impact the landscapes that we associate with our cultural or national identity are limited [2]. and steps are taken to preserve the building style, land-use and character of the area. For example, many would associate the Lake District National Park with William Wordsworth, traditional rustic farming, the rolling hills of England and relaxing around the lakes than they would with untouched nature. It could be argued that most British, and to an extent European national parks are therefore preserving a human-influenced landscape that we feel is in danger rather than a wilderness. Economics can be one of the biggest driving factors in establishing new parks, revenue from tourism has helped create parks in Australia, the UK and Canada during the last 20 years[2].

The Lake District, UK, has been a popular destination long before it was designated a national park in 1951. William Wordsworth famously wrote «I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud» about the area in 1802 (photo: wikipedia)

Our Tharu guide, Raju, had his father killed by a wild elephant. (Photo: Pål Ringkjøb Nielsen)

National parks in developing countries on the other hand were often established after those in industrialised nations and while a higher proportion of the population lived rurally. Some communities therefore underwent challenges to their livelihoods, or in some cases were forcibly evicted in favour of conservation [3]. Following the establishment of the Chitwan National Park in Nepal, the Tharu people faced restrictions on the amount of biomass and fruit that could be harvested, while fishing, hunting, and the amount of grazing land were also restricted [4]. Since 1964 over 22,000 Tharu have been removed from the park. Despite initial high expectations, many Tharu found the compensatory land was inadequate in terms of soil quality, resources, location and cultural value. Additionally, the re-location has affected the community social structure by mixing indigenous and hill castes [4]. The fate of the Tharu people is just one of many examples of local people being marginalised in favour of conservation, where following resettlement the population are forced to become less self-sufficient without the natural resources they previously relied upon.

It’s not just the understanding of national parks that differ between the “North” and “South” when it comes to how conservation is perceived. There is also a large distinction on how the conservation of large mammals. Despite a population of just 35 to 52 wolves, Norway kills over 25% of the population each year, and also permits the cull of bears, wolverines and even Golden eagles that have killed reindeer [5]. The wolves are exterminated based on the risk posed to farmers and their livestock. In reality however no one has been killed by a wolf in Norway since 1800 and of the 26,512 cases where farmers were richly compensated for livestock killed by wolves in 2012, only 1809 (7%) cases presented carcasses. A further 20,000 cases were rejected by the authorities [6].

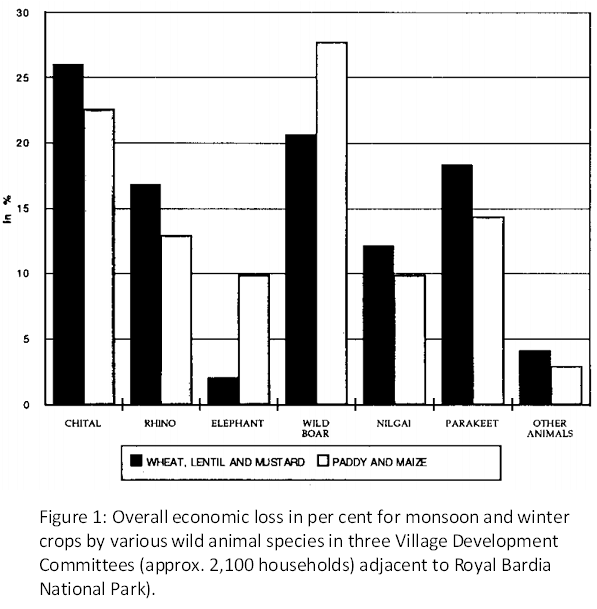

That one of the world’s richest countries can kill a “critically endangered” species seems contradictory when you consider how Norway is an avid supporter of conservation in the developing world. Human-wildlife interactions are a serious problem in Nepal where 21 people were killed by wild elephants between 2008 and 2012 [7] while crops such as rice, lentils and wheat are frequently damaged by wild animals [8]. Some have argued that if less developed countries were to use similar tactics for protecting their agricultural livelihoods there would be widespread commendation [6].

Of course, the Scandinavian countries do many great things for conservation both at home and abroad, but I think that if conservation of nature is to be addressed on a global scale then we need a global consensus of how to construe conservation. We need to decide what landscapes we are conserving and whether they should be conserved due to their importance for wildlife and nature or due to their cultural value to us and whether there should be a distinction in conservation techniques between landscapes. Similarly we cannot expect poorer nations to act on our public perception and advice concerning conserving of large mammals when we take such drastic action on curtailing animals perceived to be a threat within our own territory.

- Hannah, L., et al., Conservation of biodiversity in a changing climate. Conservation Biology, 2002. 16(1): p. 264-268.

- Woods, M., Rural geography: Processes, responses and experiences in rural restructuring. 2004: Sage.

- Brockington, D. and J. Igoe, Eviction for conservation: A global overview. Conservation and society, 2006. 4(3): p. 424.

- McLean, J. and S. Straede, Conservation, relocation, and the paradigms of park and people management – A case study of Padampur Villages and the Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Society & Natural Resources, 2003. 16(6): p. 509-526.

- Monibot, G., Norway’s plan to kill wolves explodes myth of environmental virtue, in The Guardian. 2012: London.

- McPherson, B., Den norske ulveløgnen, in Aftenposten. 2013: Oslo.

- Pant, G. and M. Hockings, Understanding the Nature and Extent of Human-Elephant Conflict in Central Nepal. 2013.

- Studsrød, J.E. and P. Wegge, Park-people relationships: the case of damage caused by park animals around the Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. Environmental conservation, 1995. 22(02): p. 133-142.