About hsu004

View all posts by hsu004

The Climate: we are changing it, and we can change it again

By Hanna Sundahl

You have probably seen by now pictures of smog engulfing major cities in China, and the pictures of burning forests in Indonesia last year. What do these have in common? They are large-scale human-induced (anthropogenic) changes. The former is attributed to the large amounts of coal produced for the Chinese energy sector (Bloomberg, 2015). The latter scenario is occurring because of a combination of predictable and unpredictable causes: large tracts of forest are burned to make way for large-scale production of e.g. oil palms (used for cooking oil, snacks, and cosmetics, among other things), but the periodic, unpredictable climate event El Niño we are experiencing right now also increases drought across the peninsula, reducing the amount of rain that otherwise extinguishes these fires (Balch, 2015).

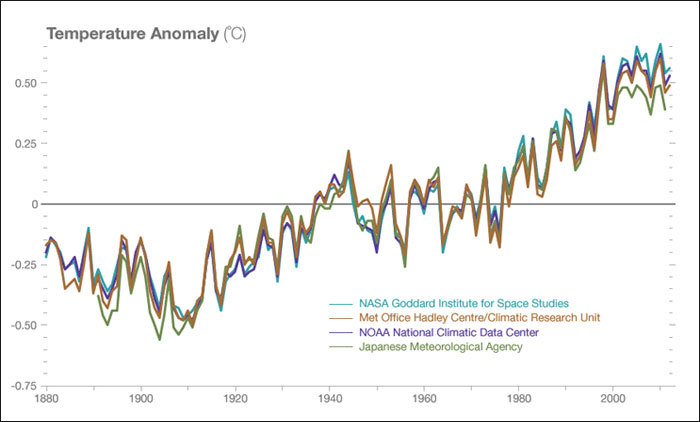

But while this should show you at what scales we can change the planet, climate skeptics will argue that global climate change is entirely natural, not anthropogenic. Climate change does indeed occur continuously, and we can observe changes until around 400,000 years ago by looking at the gas percentages in trapped air bubbles in ice cores such as those in Antarctica (Barnola, et al., 2003). But evidence from this as well as from present-day observations like those made at the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii show atmospheric CO2 content and the average global temperature have been on a growing trend ever since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s, and the last decade has the been the warmest on record, see figure below (IPCC, 2014). By now, most climate scientists (97%) agree that we are seeing global warming and that this can largely be attributed to anthropogenic fossil fuel burning and land-use change (NASA, 2016). But it’s not entirely the amount of CO2 we’re releasing, but the rate that should make you turn off your TV, hop off your couch, and run over to that climate march. Digging up and burning fossils that have been sequestered over some million years disrupts the slow natural carbon cycle (IPCC, 2014). Now, considering humans have been so adept at extracting all this in such a short time, it makes sense to think that the earth is “fighting back”, trying to reach homeostasis much like a living organism.

Temperature data from four international science institutions, showing an increasing trend and record warmth for the past decade. Data sources: NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, NOAA National Climatic Data Center, Met Office Hadley Centre/Climatic Research Unit and the Japanese Meteorological Agency. Image © NASA. Retrieved from: http://climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus/

Climate change affects us in all sorts of ways: extreme weather events increase in frequency, food security and shelter become threatened, which in turn worsens poverty and health, and destabilizes social and political infrastructures. But to fight against this, we have to be frank about what the solution is: stop using fossil fuels and start using renewable, cleaner energy. Our reluctance to switch to more renewable energy sources exists in part due to misinformation. For example, solar panel and wind turbine production are actually declining in cost, and, once installed, are essentially free, unlike plantations running on fossil fuels. Production is continuously increasing, including in Saudi Arabia and China, the latter mainly to deal with the health-damaging smog problem (Lewis, 2015). As the movie “This Changes Everything” states, perhaps the status quo Capitalism is a major source of this evil?

Al Gore sums up the motivation to fight against climate change more succinctly than I can in one blog post with his newest TED talk “The case for optimism on climate change”, which I urge you all to see → http://tinyurl.com/hpd4yxp. He lists all the challenges that I mentioned and more, but also brings to light the motivating fact that we CAN change and ARE in fact heading in the right direction to a more renewable, sustainable energy regime.

So it’s not actually the lack of investment or knowledge holding us back, though public outreach can always be improved. As cheesy as it sounds, we just need to be able to BELIEVE it is possible to slow down anthropogenic climate change.

Perhaps it’s alright for some to think we will become the next dinosaurs anyway, let’s just go about with business as usual…but, why hasten the extinction process? I don’t believe it’s a time to give up; consider instead the optimism in seeing the combined forces of people making their voices heard together with research and investment made into more sustainable solutions for the future.

References

Balch, O. (2015, November 11). Indonesia’s forest fires: everything you need to know. Retrieved from Guardian sustainable business: http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/nov/11/indonesia-forest-fires-explained-haze-palm-oil-timber-burning

Barnola, J. M., Raynaud, D., Lorius, C., & Barkov, N. I. (2003). Historical CO2 record from the Vostok ice core. Trends: A Compendium of Data on Global Change. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, U.S.A.

Bloomberg. (2015, December 30). China to Halt New Coal Mine Approvals Amid Pollution Fight. Retrieved from Bloomberg Business: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-12-30/china-to-suspend-new-coal-mine-approvals-amid-pollution-fight

IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva: IPCC.

Lewis, A. (Director). (2015). This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein [Motion Picture].

NASA. (2016). Scientific consensus: Earth’s climate is warming. Retrieved from Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet: http://climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus/

Why we should care more about our coasts: coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass meadows in the tropics

By Hanna Sundahl

When you think of a tropical ocean, you probably think of pristine, turquoise waters, with colorful reefs spread below the surface teeming with fish and other stunning marine life. Indeed, this is what a healthy tropical coral reef should look like. Even though coral reefs cover less than 0.1% of the ocean surface area, they sure pack a punch in terms of biodiversity, with vertebrate species densities far greater than those found in rainforests (Kaiser, et al., 2011).

The coral reef at Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef, in all its splendor. (c) Sarah Norris, Published in Voyeur January 2014. Retrieved from: https://travel.virginaustralia.com/nz/voyeur/heavenly-heron-island

Coral reefs are a vital habitat for a number of reasons. Not only do they provide food, shelter and breeding grounds for marine life, reefs are also important for us people, since not only do they give us food (in many areas fish is the main source of protein), they also slow down wave action and serve as inexpensive coastal protection (Hoegh-Guldberg, et al., 2007). Coral reefs also have the potential to replace rainforests as the new “medicine cabinet” of nature to provide natural chemicals that can treat all sorts of human ailments (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). And of course, they attract millions of tourists coming to dive and snorkel, making them a very important source of income for coastal regions (IPCC, 2014).

However, coral reefs are only part of the picture. They also have less well-known “sister ecosystems”, namely the muddy-looking mangrove forests and the seemingly simple-looking seagrass meadows. These habitats provide essential nursery spots for the juveniles of many of the fish we see while diving in coral reefs, including sweetlips, snappers, and surgeonfish (our beloved Dory) (Nagelkerken, et al., 2000). With their complex root systems keeping sediments in place, mangroves and seagrasses also help serve as coastal protection (Kaiser, et al., 2011).

Mangrove forest in Papua, Indonesia. (c) Photo credit: Ethan Daniels. Retrieved from: http://blog.nature.org/science/2013/10/11/new-science-mangrove-forests-carbon-store-map/

Seagrass meadow with predatory fish lurking above. (c) NOAA, Heather Dine. Retrieved from: http://www.amnh.org/education/resources/rfl/web/oceanguide/key.html

These three connected habitats are havens of biodiversity, sources of food and security for people, and all of them are unfortunately threatened by human coastal development. Mangroves and seagrass meadows suffer from chemical runoffs from shrimp aquaculture and farming nearby, as well as from outright mechanical destruction for land reclamation (American Museum of Natural History). Coral reefs also suffer from farmland fertilizer runoff that can cause eutrophication, leading to a habitat dominated by fast-growing algae rather than coral (Hoegh-Guldberg, et al., 2007). Careless tourists kicking and removing corals and associated living organisms, and irresponsible fishing practices like dynamite and cyanide fishing, add further pressures to these fragile ecosystems.

Considering their importance and vulnerability, protective measures need to be taken for these habitats. One such measure is to create strictly regulated Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), where limited or no human development can occur, and where visitors have to be extremely careful and considerate (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Such protected areas act as a refuge, a safe space in which biodiversity thrives, and act as a source population for re-colonization of surrounding habitat. Top priority areas are those with high endemism, where the habitat is still very intact, or that are important for feeding and breeding of long-distance migrators like manta rays or whales. The cost of maintaining MPAs is outweighed by their increased attractiveness for responsible divers and tourists in love with these healthy marine habitats.

MPAs, together with other regulations such as fishing quotas, can allow future generations to acquire the protein they need from the sea, live at the coast, and thrive on responsible tourism. Of course, there are global threats that cannot be kept out of these parks – notably ocean warming and acidification – which is why we also need to pay attention to our carbon emissions problem, the topic of my next post. But with this, I, as a diver and marine biologist, urge you to be a responsible tourist and citizen of the world and care about these fragile, yet incredibly important habitats.

References

American Museum of Natural History. (n.d.). Mangrove Threats and Solutions. Retrieved from Mangroves: the Roots of the Sea: http://www.amnh.org/explore/science-bulletins/bio/documentaries/mangroves-the-roots-of-the-sea/mangrove-threats-and-solutions

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., et al. (2007). Coral Reefs Under Rapid Climate Change and Ocean Acidification. Science, 318(1737), 1737-1742.

IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. Geneva: IPCC.

Kaiser, M. J., et al. (2011). Mangrove Forests and Seagrass Meadows. In Marine Ecology: processes, systems, and impacts (2nd Ed) (pp. 277-303). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaiser, M. J., et al. (2011). Coral Reefs. In Marine Ecology: processes, systems, and impacts (2nd Ed) (pp. 305-323). New York: Oxford University Press.

Nagelkerken, I., et al. (2000). Importance of Mangroves, Seagrass Beds and the Shallow Coral Reef as a Nursery for Important Coral Reef Fishes, Using a Visual Census Technique. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 31-44.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Marine Protected Areas. Retrieved from http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/ecosystems/mpa/

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Medicine. Retrieved from NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program: http://coralreef.noaa.gov/aboutcorals/values/medicine/